Evolution of the Transplant Waiting List | FMCNA

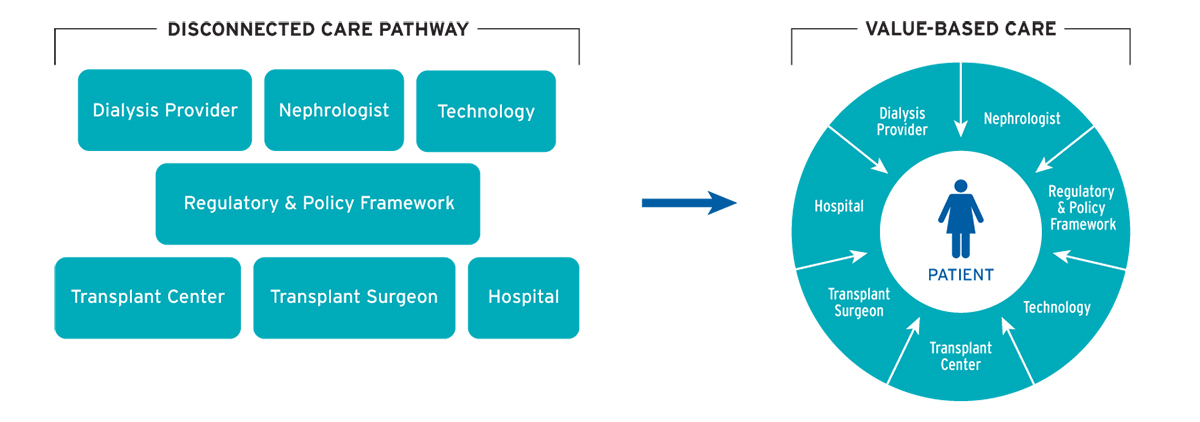

The complex metrics and practices that govern the transplant waiting list are undergoing significant change. There are many factors driving this evolution in selection criteria, including reforms in Medicare regulations and the kidney allocation system. However, in spite of these major changes, dialysis providers, nephrologists, transplant centers, regulators, and payors still have too many competing interests. Better transplant access requires a vision and framework that mandates open communication and active collaboration between all stakeholders.

Many nephrologists and patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD) may be forgiven for thinking of the transplant waiting list as a fairly simple concept rendered mysterious by layers of complexity. For patients referred for transplant (or clinicians tracking such referrals), it can be a surprise to discover that being listed is an ongoing process, rather than a discrete event. Staying "active" on the waiting list involves frequent reevaluations, virtual and in-person check-ins, and retesting. In addition, the patient must provide a series of updates on physical issues, social support, and financial health.

A nephrology clinic or dialysis facility has little insight into the transplant surveillance system. It is often difficult to discern exactly what is tracked, how it is tracked, or when a patient status is changed due to a variance from the prevailing wait-list criteria. The ability of the dialysis facility or nephrology practice to reliably communicate with a transplant center about referred and wait-listed patients is often piecemeal at best. Why?

In most markets, nephrology practices, dialysis providers, and transplant centers operate independently of each other. The historically siloed division of labor between these three stakeholders yielded separate institutions, regulatory frameworks, technology platforms, and, ultimately, different organizational cultures. Put simply: Dialysis providers and transplant centers do not fully understand each other, and in today's regulatory framework, they do not have a stake in each other's success. Recently, the regulatory milieu has shifted toward apportioning some regulatory risk on dialysis facilities for transplant-related quality metrics. However, unless the barriers between dialysis providers, nephrologists, and transplant centers are deliberately lowered, each stakeholder will advocate for their own quality metrics processes, which may not yield a positive impact on care coordination or meaningfully expand access to transplantation.

REGULATORY RISK

Historically, kidney transplant centers were held to narrowly defined risk-adjusted Medicare benchmarks for patient and graft survival rates. In the event a center failed to meet regulatory requirements, the failure could result in penalties such as public sanctions, being required to enter into an expensive Systems Improvement Agreement to continue to qualify for Medicare reimbursement, and losing private payor contracts for all solid-organ transplants in their program. Medicare's methodology employed to adjust risk was the subject of significant debate and criticism at the time of implementation.1 With ongoing concerns about regulatory sanctions by Medicare, some transplant centers elected to limit exposure to regulatory risk by:

- Limiting acceptance of higher-risk organs2

- Intensively surveilling active wait-listed candidates, while implementing lower thresholds for wait-list inactivation and removal

- Instituting more conservative candidate selection criteria, effectively excluding higher-risk transplant candidates from the waitlist

Transplant centers following a risk-averse approach often achieved high patient and graft survival rates; however, the approach also resulted in the unintended consequences of reducing patient access to the wait list and increasing organ discard rates.

To address these concerns, Medicare liberalized the thresholds

for regulatory sanctions based on outcomes. A first step in that direction was raising the flagging thresholds for patient and graft survival. Most recently, in September 2018, Medicare proposed the organization substantially step back from the regulatory oversight of transplant centers, shifting that role back to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), under the supervision of the Department of Health and Human Services.3 Whether this regulatory shift will improve access to the waiting list or reduce rates of organ discard remains to be seen.

But, even as Medicare appears to be de-escalating its regulatory presence in transplant as of Q4 2018, individual private payors continue to administer Center of Excellence criteria, which is essentially a series of patient and graft survival outcome metrics like Medicare. In addition, the private payor Center of Excellence program also benchmarks transplant centers using unique metrics such as a transplant rate.4 The transplant rate is the number of transplants performed at a center per 100 patient-years on the waiting list. The significance of the measure is that centers with a higher transplant rate ostensibly deliver beneficiaries to transplant faster than centers with a lower rate. The catch is that patients who are listed "inactive" count toward the total number of patient-years in the denominator. Centers with a high number of patients listed "inactive" will have an artificially lower transplant rate. Private payors view lower transplant rates unfavorably, and transplant centers might have a reason to adjust their wait-list policies to avoid misinterpretation of the result of the transplant rate methodology.

New to the policy landscape is a quality metric that is designed to hold dialysis facilities accountable for increasing access to transplantation. After much discussion and public comment, Medicare will hold facilities accountable for the Percentage of Prevalent Patients Waitlisted (PPPW). There are several notable features of PPPW as a quality metric:

- PPPW measures rates of wait-listing, not rates of referral. A unit that refers many patients but lists (too) few will fall afoul of the PPPW metric.

- Referral is within the power of the medical director and attending physician of the dialysis unit, but the decision to wait-list is not.

- Transplant centers, under pressure to improve their transplant rate metric, may choose not to list medically appropriate candidates for transplant until they have accrued sufficient waiting time to be close to the top of the list.

In short: The PPPW is a quality metric that is not wholly within the control of the facility and its medical leadership. The PPPW conflicts with competing pressures on transplant centers to improve their transplant rate metric by reducing waiting lists to include just those patients likely to be transplanted in a short period of time after listing.

COMING ATTRACTIONS

Finally, major changes may be coming to the kidney allocation system. New liver allocation rules were approved by the joint OPTN and United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Board of Directors in December 2018, though implementation is currently on hold due to ongoing federal litigation as of June 2019. If implemented, liver sharing would shift away from small geographic donor service areas surrounding organ procurement organizations. The new rules require livers to be shared within 500 nautical miles of the procurement hospital. This would result in livers being shipped all over the country, with most of them going to large, population-dense metropolitan areas at the expense of smaller cities and rural areas. The stated reason for this change was to address geographic disparities in access to liver transplantation.

A recent call for public comment from OPTN/UNOS on a proposal to revise the kidney allocation rules along the same lines makes it clear that if very broad geographic sharing is implemented for livers, it should be implemented for kidneys as well.5 The Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) has published projections of how organ allocation will change for various markets and geographies based on several different allocation models.6 Under the new allocation system, kidneys would be exported from areas of lower population density to areas of very high population density, reducing the total number of kidney transplants from deceased donors allocated to candidates listed at centers located in less populated areas. The combination of more organs exported from less to more populated areas with pressure on transplant centers to reduce their waiting lists to improve their transplant rate metric will render dialysis facilities in less populated areas unable to improve their PPPW. Improvements in care coordination will require regulators and payors to engage in more effective metrics coordination.

A BETTER WAY FORWARD

An article published in the American Journal of Transplantation outlined a vision for a reimbursement model that would align the interests of dialysis providers, nephrologists, transplant centers, regulators, and payors.7 While the proposal was framed around the ESRD Seamless Care Organization (ESCO) shared-savings model, the article identified ways in which Fresenius Medical Care North America (FMCNA) can break down clinical care silos, expand access to transplantation for patients, and ensure current and future transplant candidates remain medically, socially, and financially positioned to succeed after transplantation (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 | New model puts patient at center of care

The vision includes:

- Implementing a common information technology platform

Provide all stakeholders real-time tracking of the status of transplant referrals, patient progress in the transplant evaluation process, wait-list activity status, and status updates once a patient is active on the list.

- Supporting quality metrics that expand patient access to transplant and improve wait-list management, rather than box-checking

Private payors and regulators should abandon the transplant rate and PPPW metrics in favor of metrics that reward collaborative, integrated wait-list management programs between transplant centers and dialysis facilities.

- Inviting transplant personnel into Fresenius Kidney Care dialysis facilities

Facilitate chart review, chairside in-person transplant education, and participation in monthly multidisciplinary continuous quality improvement (CQI) meetings. Doctors, nurses, social workers, and patient care technicians know Fresenius Kidney Care patients and have the tools and insights to position patients to succeed with transplant.

- Using system solutions to identify and overcome surmountable barriers to transplant

Many Fresenius Kidney Care patients are medically suitable but not socially, psychologically, or financially readyfor transplant. Building on Fresenius Kidney Care experience operating ESCOs in more than 30 markets around the country, FMCNA is committed to partnering with local transplant centers to create support programs for patients to find novel ways to bridge gaps in social support, transportation, and medication adherence.

- Pressuring transplant centers to do their part

High rates of organ discard do not serve patients well. Transplant centers must be encouraged and supported to do their part to increase access to transplantation by transplanting higher risk organs.

Effective wait-list management can increase the number of patients with access to kidney transplantation. Only with active, transparent collaboration between nephrologists, transplant programs, dialysis providers, and patients can a rational, consistent, and scalable delivery system be designed.

Meet Our Experts

BENJAMIN HIPPEN, MD, FASN, FAST

Medical Director, Fresenius Kidney Care; Partner, Metrolina Nephrology Associates, P.A.

Benjamin Hippen is a general and transplant nephrologist with Metrolina Nephrology Associates, P.A., and is a Clinical Professor of Medicine at the UNC Chapel-Hill School of Medicine. Dr. Hippen serves as the associate medical director of the kidney and kidney-pancreas transplant program at Atrium Health, and he serves as medical director of a Fresenius Kidney Care in-center hemodialysis and home therapies facility in Charlotte, N.C.

FRANKLIN W. MADDUX, MD, FACP

Global Chief Medical Officer, Fresenius Medical Care

Dr. Franklin W. Maddux's distinguished career encompasses more than three decades of experience as physician, expert nephrologist, technology entrepreneur, and health care executive. He previously served as Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Officer for Fresenius Medical Care North America and joined Fresenius Medical Care in 2009 after the company acquired Health IT Services Group, a leading electronic health record (EHR) software company founded by Maddux. He developed one of the first laboratory electronic data interchange programs for the US dialysis industry and later created one of the first web-based EHR solutions, now marketed under Acumen Physician Solutions. A practicing nephrologist for nearly two decades, Dr. Maddux graduated with his baccalaureate in mathematics from Vanderbilt University and holds his MD from the School of Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he holds a faculty appointment as clinical associate professor. His writings have appeared in leading medical journals, and his pioneering health care information technology innovations are part of the permanent collection of the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution.

References

- Hippen BE. Debating organ procurement policy without illusions. Am J Kidney Dis 66(4): 577-82.

- Bowring MG, Massie AB, Craig-Schapiro R, Segev DL, Nicholas LH. Kidney offer acceptance at programs undergoing a Systems Improvement Agreement. Am J Transplant 2018 Sep;18(9): 2182-88.

- National Archives. Medicare and Medicaid programs; regulatory provisions to promote program efficiency, transparency, and burden reduction. Federal Register, Sept. 20, 2018. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/09/20/2018-19599/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-regulatory-provisions-to-promote-program-efficiency-transparency-and.

- Fay, Koren. Transplant rate—a new metric to worry about? XynManagement blog, n.d. https://xynmanagement.com/transplant-rate-new-metric-worry/.

- Castro S, Fox A. Eliminate the use of DSAs and regions in kidney and pancreas distribution. OPTN/UNOS Kidney and Pancreas Committees Concept Paper, 2019. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2802/kidney_pancreas_publiccomment_20190122.pdf.

- Gustafson S, Weaver T, Salkowski N, et al. Analysis report: data request from the OPTN Kidney Transplantation Committee: provide KPSAM simulation data on effect of removing DSA and region from kidney/pancreas/kidney-pancreas organ allocation policy. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, Dec. 7, 2018. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/media/2768/kp_analysisreport_20181207.pdf.

- Hippen BE, Maddux FW. Integrating kidney transplantation into value-based care for people with renal failure. Am J Transplant 2018 Jan;18(1):43-52.