Understanding Dialyzer Types

ANATOMY OF A HOLLOW FIBER DIALYZER

A hollow fiber dialyzer bundle comprises 7–17 x 103 semipermeable hollow fibers that allow solute and fluid transfer between blood and dialysate. Typical fibers have an internal diameter of 180–200 microns and wall thickness of 30–40 microns, yielding 1.0–2.5 m2 of surface area. Fibers may have features, such as undulations, to distribute dialysate flow evenly through the fiber bundle.

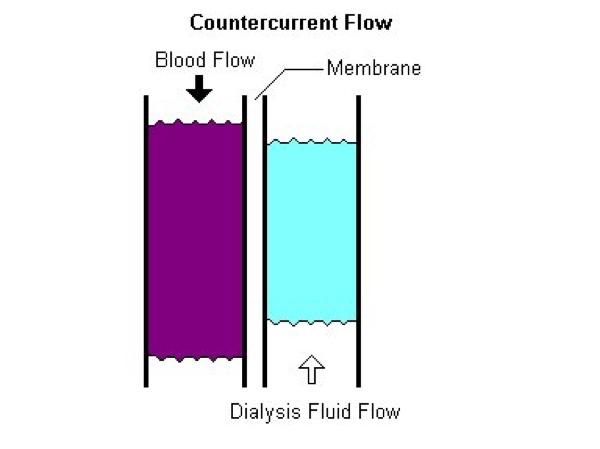

The fiber bundle is enclosed in an outer housing that forms the dialysate compartment. The header is the space enclosed by the end cap and the polyurethane potting material that holds the hollow fibers and forms a barrier between the blood and dialysate compartments. Headers channel blood from the dialyzer inlet into the membrane fibers and from the membrane fibers into the dialyzer outlet. The end caps can be removed from some dialyzers. In those cases, an O-ring is used to form a seal between the end cap and the potting material. Blood and dialysate flow in opposite directions (countercurrent flow) to maximize diffusive solute transfer.

MEMBRANE MATERIALS AND BIOCOMPATIBILITY

Non-synthetic membranes are derived from natural materials such as cotton and are less biocompatible than synthetic membranes. Biocompatibility can be improved by substituting hydroxyl groups, which reduces the ability of cellulose membranes to activate complement and cause leukopenia. Moieties that have been substituted for cellulose include acetate, diethylaminoethyl (DEAE), benzyl, polyethyleneglycolic, and vitamin E. The resultant membranes are referred to as modified cellulose membranes. Only cellulose diacetate and cellulose triacetate membranes remain in widespread clinical use in the U.S. Modified cellulose membranes can be either high flux or low flux.

Synthetic membranes are commonly used in the U.S. These include:

- PSf (polysulfone and a family of polysulfone blends) offer good biocompatibility and protection from endotoxins

- PES (polyethersulfone) which is a blend of hydrophobic base polymers with good biocompatibility and less albumin loss

- CTA (cellulose triacetate) with increased solute permeability especially for beta-2 microglobulin

- PMMA (polymethylmethacrylate) with increased adsorption properties to enhance removal of some inflammatory molecules

- PEPA (PES plus polyarylate) with enhanced endotoxin protection

- EVAL (ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymers) with low inflammatory impact

- PAN (polyacrylonitrile) with good biocompatibility and enhanced fluid removal due to hydrophilic properties

DIALYZER PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS

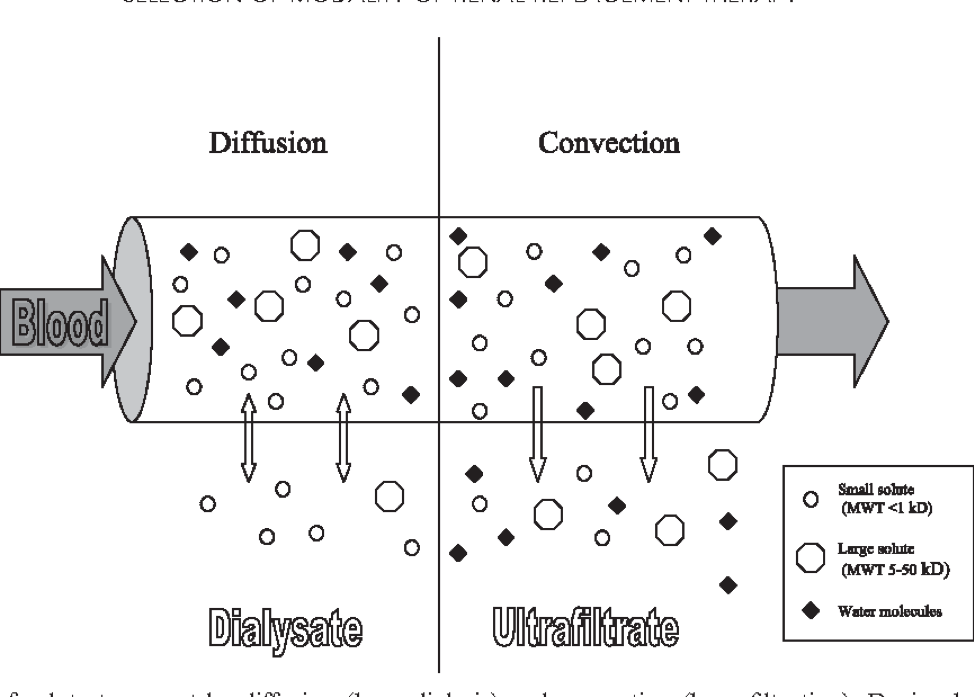

The primary mode for removal of small solutes (e.g., urea) by hemodialysis is diffusion down the concentration gradient between plasma water and dialysate. Transfer of small solutes (e.g., HCO3-) from dialysate to plasma water also occurs primarily by diffusion. The rate of diffusion is a function of the thickness and porosity of the membrane and the diffusivity of the solute in the membrane. It is expressed as the diffusion coefficient of the membrane for a given solute. The rate of diffusion is greatest for small molecules and the diffusivity of a solute in a membrane decreases logarithmically as solute size increases. The rate of diffusion also decreases as membrane thickness increases and porosity decreases.

The primary mode for removal of large solutes by hemodialysis is convection, as water containing these solutes flows from plasma to dialysate in response to a hydraulic pressure gradient. The rate of convection is a function of the ultrafiltration rate, size of the solute and pore size of the membrane. The ability of a solute to pass through the pores of a membrane is expressed as the sieving coefficient of the membrane for a given solute. A solute with a sieving coefficient of 1.0 passes freely through the membrane while the membrane is impermeable to a solute with a sieving coefficient of zero.

Convection provides better removal of large solutes than diffusion because the decrease in sieving coefficient with increasing solute size is less marked than the decrease in diffusion coefficient. Dialyzer manufacturers usually provide sieving coefficients of albumin, beta-2 microglobulin, myoglobin, and lysozyme as parameters of albumin leak and convective performance.

ADSORPTION AND HYDROPHOBICITY

The nature of the polymers used in a membrane determines the membrane's tendency to repel water, referred to as hydrophobicity. In general, cellulose membranes are less hydrophobic while many synthetic polymer membranes are more hydrophobic. Alloying with hydrophilic polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) decreases the hydrophobicity of the synthetic membrane.

During hemodialysis, proteins may adsorb to both the planar surface of the membrane and the inner surface of its pores. The adsorbed protein may decrease diffusive and convective removal of other solutes by effectively reducing the pore size of the membrane. Hydrophobic surfaces adsorb serum proteins, which can contribute significantly to low-molecular-weight protein removal by some membranes.

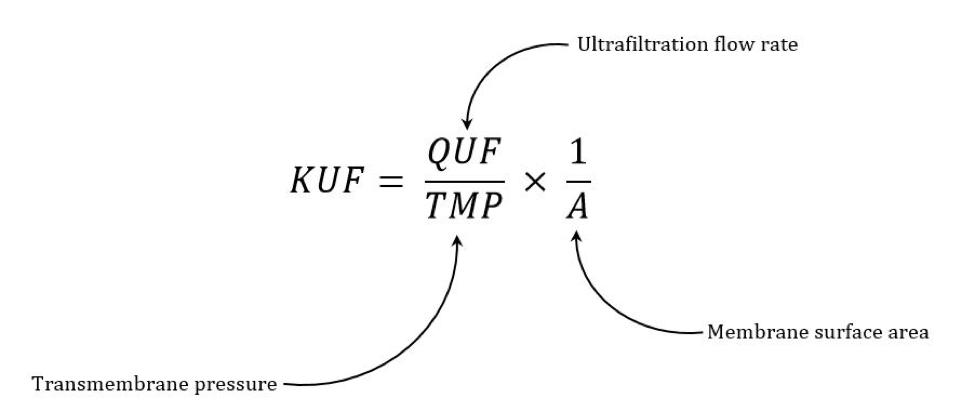

ULTRAFILTRATION COEFFICIENT (KUF)

The ultrafiltration coefficient (Kuf) is a measure of the water permeability of a membrane and is usually expressed in mL/hr/mm Hg. The formula for determining Kuf is:

Kuf = QUF (ml/hour)/TMP (transmembrane pressure)

For example, if a dialysis machine generated a transmembrane pressure (TMP) of 200 mm Hg, a dialyzer with a Kuf of 12 ml/hr/mm Hg would produce an ultrafiltration rate of 12 ml/hr/mm Hg x 200 mm Hg = 2.4 L/hr.

Kuf is relatively unimportant in modern HD machines with volumetric UF control, although dialyzers with a higher Kuf may have higher clearance and sieving coefficient values as well.

HIGH PERFORMANCE AND MIDDLE MOLECULAR CUT-OFF MEMBRANES

High performance membrane (HPM) is a classification used in Japan to identify hollow fiber dialyzers with an advanced level of performance. HPM membranes increase removal of protein-bound uremic toxins from albumin leak and also increase removal of middle- to large-molecular-weight solutes, including β2-macroglobulin, through increased diffusion and adsorption. The Japanese Society of Dialysis Therapy (JSDT) recommends that pores in HPM be large enough to allow slight losses of albumin, at a rate of <3 g/session with a blood flow rate of 200 ml/min and a dialysate flow rate of 500 ml/min. The hypothesis is that larger pores approximate the glomerular filtration of uremic toxins and albumin in the human kidney, while some protein leakage may enhance albumin turnover. No clinical outcomes data support this at present.

DIALYZER CLEARANCE

Diffusive solute removal by a dialyzer is usually described in terms of clearance (K), which is defined as the volume of blood completely cleared of a given solute per unit time. Unlike the in-vitro clearance of a specific solute (KoA), which is supplied by the manufacturer and determined in vitro, K is dependent on both the blood and dialysate flow rates. For this reason, it is not a good means of characterizing innate dialyzer performance. All dialyzers report in-vitro clearance values, and the actual in-vivo clearances are typically lower than the in-vitro values for the same blood flow rate (Qb) and dialysate flow rate (Qd) combination.

DIALYZER SELECTION

Kt/Vurea is the most validated and commonly measured parameter of dialysis adequacy despite its limitations1. Some clinicians use a low-efficiency dialyzer and/or shorter time and low blood and dialysate flow rates during the initial hemodialysis treatment(s) to avoid dialysis disequilibrium syndrome. In order to determine the dialyzer that will provide a target Kt/Vurea first calculate the total body water (TBW = Urea volume of distribution) either anthropometrically (e.g., Watson for adults, Mellits-Cheek for children) or, preferably, via bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) when available to solve the Kt/V equation for either t (duration of treatment) or K (dialyzer clearance for a given Qb/Qd).

For example, Mr. Doe has a V of 40L and the target Kt/V is 1.4:

Kxt/V or Kxt/40 = 1.4

Kxt = 40 x 1.4 = 56 L or 56,000 ml

Let's assume you have a dialyzer that has in-vitro Kurea of 250 ml/min at Qb/Qd of 300/500 ml per minute. This clearance should be multiplied by 0.85, which is about a 15% adjustment from in-vitro to in-vivo clearance. Therefore, K would be 250 x 0.85 = 212.5 ml/min.

The duration of treatment, or t, can now be determined:

212.5 x t = 56,000

t = 56,000/212.5 = 264 minutes (4 hours 24 mins). This time can be reduced by choosing a bigger dialyzer or increasing Qb and Qd.

On the other hand, if you know the duration of treatment that you are going to prescribe (let's assume 4 hours or 240 minutes), you can solve for the Kurea needed to deliver Kt/Vurea of 1.4.

K x 240 = 56,000

K = 56,000/240 = 233 ml/min

In-vitro to in-vivo conversion = 233/0.85 = 274 ml/min

So, you will need a dialyzer with published in-vitro urea clearance of 274 ml/min at a Qb/Qd of 300/500 ml/min for this patient.

It is important to recognize a few points about these calculations:

- You can have different Qb/Qd, such as 400/600 or 500/800 ml/min, and should use them in these calculations.

- Anthropometric TBW calculations overestimate V, therefore, the delivered Kt/Vurea may be higher than the calculated one.

- Total delivered dose may have a contribution from residual kidney function, which is not accounted for in these calculations.

- At best, this calculation provides you with a starting point, and adjustments might be needed based on the measured Kt/Vurea lab values.

- Currently, there is no evidence to suggest that adequacy targets should be modified for different etiologies of ESRD, except in special circumstances such as pregnant patients who need more frequent or daily HD with additional adjustment to the dialysate composition given their special physiological needs.

- It would be prudent to avoid delivering high clearances in patients with liver failure or others who may be at higher risk of increased intracranial pressure such brain trauma or surgery.

Recommended Related References

- Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study Group. Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2002 Dec 19;347(25):2010-9. PubMed PMID: 12490682

- Membrane Permeability Outcome (MPO) Study Group. Effect of membrane permeability on survival of hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 Mar;20(3):645-54. PMID: 19092122

- Kirsch AH, Lyko R, Nilsson LG, et al. Performance of hemodialysis with novel medium cut-off dialyzers. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017 Jan 1;32(1):165-172. PubMed PMID: 27587605

- Laville M, Dorville M, Fort Ros J, et al. Results of the HepZero study comparing heparin-grafted membrane and standard care show that heparin-grafted dialyzer is safe and easy to use for heparin-free dialysis. Kidney Int. 2014 Dec;86(6):1260-7. PubMed PMID: 25007166

- Lowrie EG, Li Z, Ofsthun N, Lazrus JM. Body size, dialysis dose and death risk relationships among hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1891-7.