ANTIBIOTIC STEWARDSHIP

Fresenius Medical Care North America (FMCNA) has established an antibiotic stewardship program to help minimize the unintended consequences of antibiotic use in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Building on existing research, FMCNA is looking at how to optimize and ultimately standardize the practice of antibiotic selection, dose, duration, and route of administration. To accomplish this goal, the stewardship program is exploring a range of strategies, including narrowing the antibiotic spectrum based on culture results and greater involvement of clinical pharmacists in local care teams.

Stewardship is defined in Webster’s dictionary as the conducting, supervising, or managing of something—especially the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one’s care. Stewardship is an important concept within the realm of medicine, and it is a concept with which all members of the renal care team are intimately familiar. The ESRD care team is entrusted with the care of a population of patients with a substantial disease burden. That disease burden leads to and often includes the development of infections.

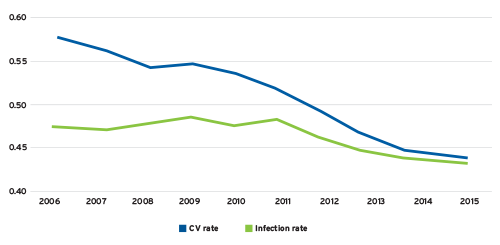

According to the 2017 United States Renal Data System Annual Data Report, the adjusted all-cause hospitalization rate for the ESRD population has dropped from 2.03 in 2006 to 1.70 in 2015.1 Although hospitalizations due to cardiovascular disease have declined sharply over the past decade, the rate of infection-related hospitalizations remains relatively flat (Figure 1). Infection now accounts for approximately the same number of hospital admissions as cardiovascular disease.

FIGURE 1 | Cause-specific hospitalization rates

Antibiotic stewardship is a relatively new concept whose roots can be traced to the acute care setting. A recent consensus statement defined antibiotic stewardship as “coordinated interventions designed to improve and measure the appropriate use of antibiotic agents by promoting the selection of the optimal antibiotic drug regimen including dosing, duration of therapy, and route of administration.”2 One of the principal goals of an antibiotic stewardship program is to avoid the unintended consequences that may occur with antibiotic use.

In a recently published study of adverse events related to antibiotic use in hospitalized patients, the authors note that 20 percent of the patients exposed to at least 24 hours of oral or IV antibiotics experienced one or more adverse events.3 Antibiotic stewardship creates the opportunity to reduce the risk of:

- Drug toxicity related to the antibiotic selected

- The emergence of antimicrobial resistance

- The development of antibiotic-associated Clostridium difficile infections

- A negative impact on the patient’s microbiome4

While not entirely relevant for the outpatient dialysis setting, it is constructive to review approaches to antibiotic stewardship in the hospital setting. In 2016, the Antimicrobial Stewardship and Resistance Working Groups of the International Society of Chemotherapy proposed 10 key points to consider when prescribing antibiotics within the inpatient setting.5 Those recommendations included:

- Get appropriate microbiological samples before antibiotic administration and carefully interpret the results: In the absence of clinical signs of infection, colonization rarely requires antimicrobial treatment.

- Avoid the use of antibiotics to “treat” fever: Use them to treat infections and investigate the root cause of fever prior to starting treatment.

- Start empirical antibiotic treatment after taking cultures, tailoring it to the site of infection, risk factors for multidrug-resistant bacteria, and the local microbiology and susceptibility patterns.

- Prescribe drugs at their optimal dosing and for an appropriate duration, adapted to each clinical situation and patient characteristics.

- Use antibiotic combinations only where the current evidence suggests some benefit.

- When possible, avoid antibiotics with a higher likelihood of promoting drug resistance or hospital-acquired infections, or use them only as a last resort.

- Drain the infected foci quickly and remove all potentially or proven infected devices: Control the infection source.

- Always try to de-escalate/streamline antibiotic treatment according to the clinical situation and the microbiological results.

- Stop unnecessarily prescribed antibiotics once the absence of infection is likely.

- Do not work alone: Set up local teams with an infectious diseases specialist, clinical microbiologist, hospital pharmacist, infection control practitioner, or hospital epidemiologist, and comply with hospital antibiotic policies and guidelines.

Of course, the majority of antibiotic use today occurs in the outpatient setting. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost 270 million prescriptions for antibiotics were filled by US pharmacies in 2015, “enough for five out of every six people to receive one antibiotic prescription each year.”6 The CDC is quick to point out that at least 30 percent of those prescriptions were unnecessary.7 Within this context, recommendations have emerged regarding the establishment of outpatient antibiotic stewardship programs.8

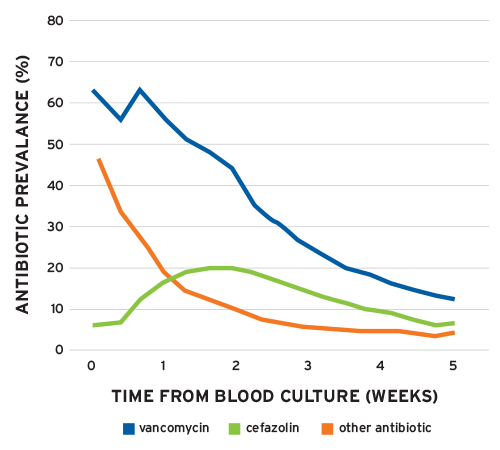

Recent studies within the ESRD population highlight the opportunities that exist for antibiotic stewardship. FMCNA’s experience with Staphylococcus was published in a 2012 article and serves to highlight one such opportunity.9 Examining data from almost 300,000 patients, the authors reported a rate of bacteremia of 15.4 per 100 outpatient years. S. aureus accounted for 4 of the 15.1 episodes per 100 outpatient years. Surprisingly, among the patients empirically treated with vancomycin who were subsequently identified as patients with methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA), over 50 percent were still receiving vancomycin one week after the index culture was obtained (Figure 2). As noted in this study, cefazolin is the preferred choice for MSSA in patients without a contraindication. Despite this, at two weeks, twice as many patients with MSSA were still receiving vancomycin compared with cefazolin. Narrowing the antibiotic spectrum based on culture results is a key tenet of antibiotic stewardship, and it is widely believed that this practice attenuates the emergence of antimicrobial resistance.

More recently, FreseniusRx collaborated with the Fresenius End Stage Renal Disease Seamless Care Organizations (ESCOs) and explored the prospect of involving a clinical pharmacist when patients develop bacteremia. During the three-month program, all positive blood cultures and the antibiotics selected were reviewed by a pharmacist. In several instances, the pharmacist recommended changes to the existing antibiotic regimen. Significantly, the pharmacist’s recommendations were universally accepted by the local care team. Many of the recommendations made by the pharmacists in this program were related to narrowing the antibiotic spectrum.

FIGURE 2 | Prevalence of vancomycin and cefazolin in ESRD patients with MSSA bloodstream infection

As noted above, much has been written about the establishment of outpatient antibiotic stewardship programs. In late 2016, the CDC published a paper entitled “Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship.”10 The authors specifically described four core elements of a successful program:

- Commitment: Demonstrate dedication to and accountability for optimizing antibiotic prescribing and patient safety.

- Action for policy and practice: Implement at least one policy or practice to improve antibiotic prescribing, assess whether it is working, and modify as needed.

- Tracking and reporting: Monitor antibiotic prescribing practices and offer regular feedback to clinicians, or have clinicians assess their own antibiotic prescribing practices themselves.

- Education and expertise: Provide educational resources to clinicians and patients on antibiotic prescribing, and ensure access to needed expertise on optimizing antibiotic prescribing.

Building on our experience and leadership in this field, FMCNA has established a formal antibiotic stewardship program. With each of the four core elements in mind, the FMCNA Antibiotic Stewardship program will serve both hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. Bacteremia will be the initial focus, with special attention directed to clinics experiencing high rates of bloodstream infections (BSI). Ultimately the program will include PD-associated peritonitis, as well as other infections requiring antimicrobial therapy. The program will support antibiotic selection, dose, duration, and route of administration. Antibiograms will be actively monitored, both to inform empiric therapy and monitor the emergence of resistance. As the program expands, antibiotic utilization and empiric choices will be reviewed, and recommendations will be made to standardize the approach where clinically warranted

Reporting bloodstream infections is a 2018 national quality measure for outpatient dialysis facilities. Reducing bloodstream infections is a laudable goal, and it is one Fresenius Kidney Care is pursuing in many ways, including by participating in the CDC’s Dialysis BSI Prevention Collaborative.11 But when serious infections occur, adding a clinical pharmacist to the care team will prove invaluable to our patients. In summary, working collaboratively with the local care team, the Fresenius Antibiotic Stewardship program will optimize the care for patients who require antibiotics and minimize the risk of unintended consequences that can accompany antibiotic utilization.

Meet Our Expert

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA

Senior Vice President, Chief Medical Officer, Integrated Care Group, Fresenius Medical Care

Terry Ketchersid has clinical oversight over FMCNA’s Integrated Care Group, which includes value-based care and pharmacy initiatives. He received his bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Austin College, his executive master of business administration from Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, and his doctor of medicine degree from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School.

References

Antibiotic Stewardship

by Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA

- United States Renal Data System. “Hospitalization,” chap. 4 in 2017 annual data report. https://www.usrds.org/2017/view/v2_04.aspx.

- Fishman N, et al. Policy statement on antimicrobial stewardship by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), and the Pediatric Diseases Society (PIDS). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:322-7.

- Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of adverse events with antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177(9):1308.

- Rashid MU, Zaura E, Buijs MJ, Keijser BJ, Crielaard W, Nord CE, Weintraub A. Determining the long-term effect of antibiotic administration on the human normal intestinal microbiota using culture and pyrosequencing methods. Clin Infect Dis 2015 May;60 Suppl 2:S77-84.

- Hara GL, et al. Ten key points for the appropriate use of antibiotics in hospitalized patients: a consensus from the Antimicrobial Stewardship and Resistance Working Groups of the International Society of Chemotherapy. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2016 Sept;48(3):239-46.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic use in the United States, 2017: progress and opportunities. Last updated October 6, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/antibiotic-use/stewardship-report/outpatient.html.

- Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA 2016;315(17):1864-73.

- Sanchez GV, Fleming-Dutra KE, Roberts RM, Hicks LA. Core elements of outpatient antibiotic stewardship. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2016

Nov 11;65(6):1-12. - Chan KE, Warren HS, Thadhani RI, Steele DJR, Hymes JL, Maddux FW, Hakim RM. Prevalence and outcomes of antimicrobial treatment for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in outpatients with ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012 Sep;23(9):1551-59.

- Sanchez et al. Core elements. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/rr/rr6506a1.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dialysis BSI Prevention Collaborative. Last updated June 15, 2016. https://www.cdc.gov/dialysis/coalition/prevention-collaborative.html.