MOVING TOWARD KIDNEY SUPPORTIVE CARE

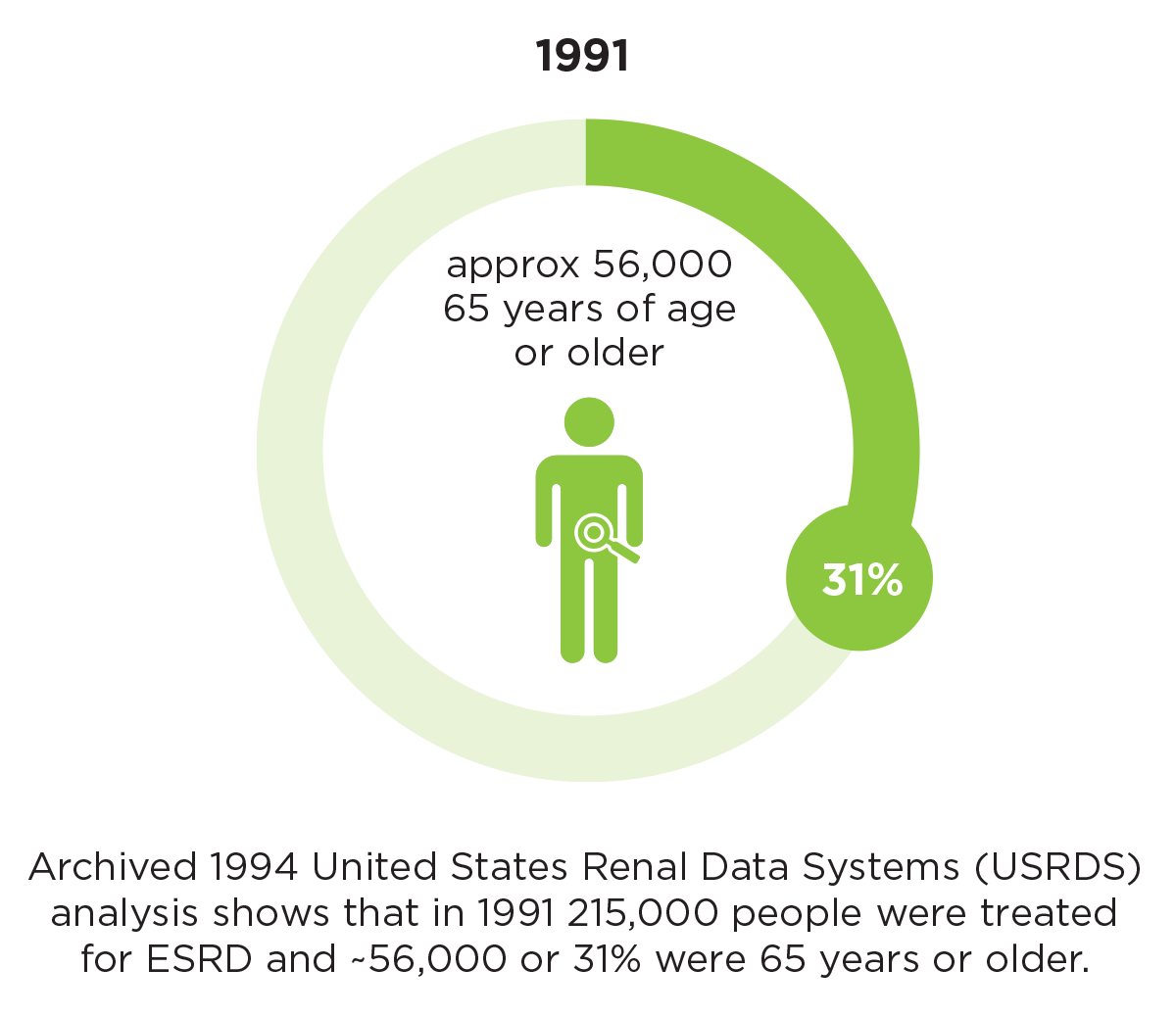

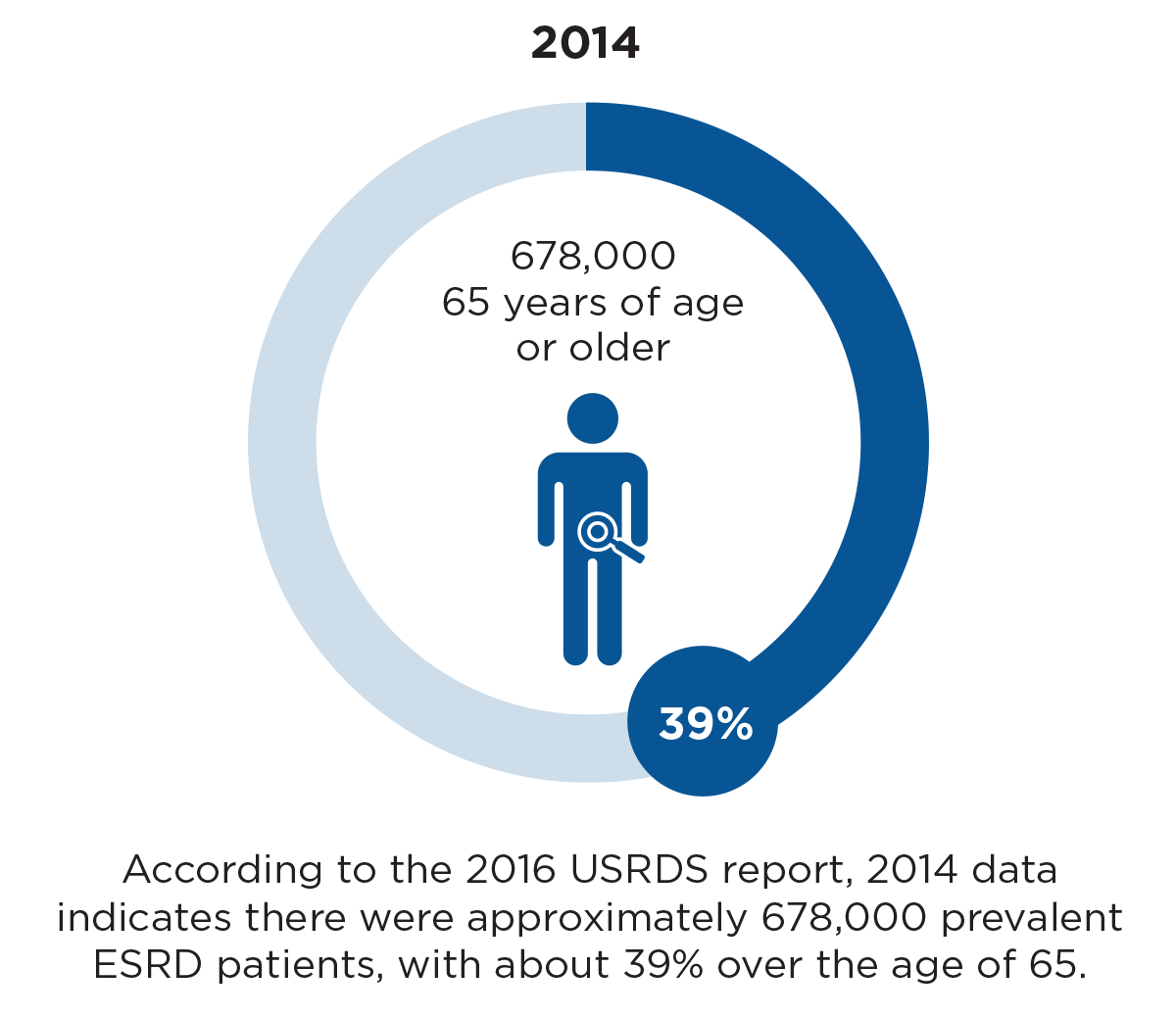

In more than four decades since the national End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) program was created and enacted as part of the Social Security amendments of 1972 (in Public Law 92-603), the number and age of patients receiving dialysis treatment have increased significantly. The 1994 United States Renal Data System (USRDS) analysis shows that in 1991, 215,000 people were treated for ESRD and around 56,000, or 31 percent, were 65 years or older.1 According to the 2016 USRDS report, in 2014 there were approximately 678,000 prevalent ESRD patients, with about 39 percent over the age of 65 (Figure 1).2 Today, the ESRD dialysis patient group is truly older and sicker.

While the dialysis patient group has significantly aged since the 1990s, clinical quality measures and a regulatory framework focused on rehabilitative dialysis have changed very little. Quality indicators associated with short- and long-term patient outcomes—including dialysis adequacy, anemia, and bone and mineral metabolism measures—are central to Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement (QAPI) activities and are tied to dialysis facility reimbursement. Standardization of care and clinical quality metrics have contributed to decreased mortality, but studies show that commensurate improvement in patient quality of life (QOL) has not occurred. Care outcomes valued by ESRD patients are not fully aligned with indicators typically measured and valued in scientific research and clinical care.3,4

Figure 1

The change in number of ESRD patients and percent of patients over age 65 years between 1991 and 2014

ESRD patients of all ages have a high physical and psychosocial symptom burden, which is accentuated by the aging dialysis population.5-7 Today, the highest rate per million for incident ESRD patients is the age group 75 years and older. This group also has the second-highest ESRD prevalence rate per million, just behind the 65-74-year-olds, according to the USRDS 2016 Annual Data Report. This aging dialysis population highlights the need for more supportive and palliative care for all dialysis patients, a need that is recognized and reviewed in recent renal care publications.8-10 The need to focus on health-related QOL is embodied in concepts around “kidney supportive care,” which includes services aimed at improving QOL through:

- Identifying patient goals

- Providing symptom management

- Providing prognostic information to patients and families to support shared decision making

- Enhancing psychological and spiritual support11

Mortality reduction in the ESRD population has been an achievement for rehabilitative dialysis programs, but for frail and elderly patients, this type of treatment may inadvertently lead to complex end-of-life care issues. The burden of intensive and inpatient care at end of life is high for ESRD patients and families.12 The 2016 USRDS data shows that 82 percent of ESRD Medicare beneficiaries have a hospital admission in the last 90 days of life with a median hospital stay of 17 days. Approximately 63 percent have an ICU or CCU admission in the last 90 days, and 34 percent have an “intensive procedure” during that time. In addition, 39 percent of ESRD patients die in the acute hospital setting, and 12.9 percent of these ESRD patients who die are 85 years of age or older.13

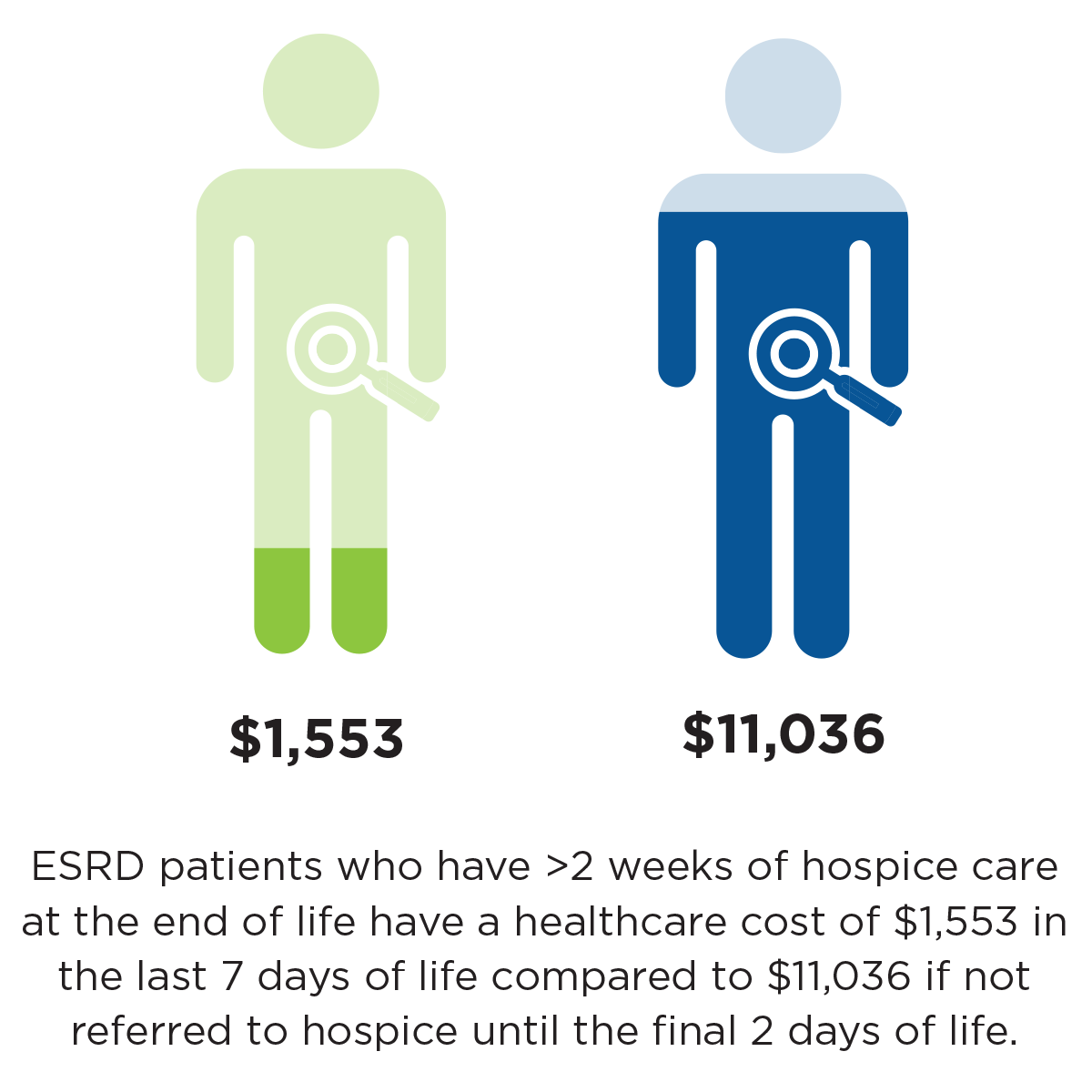

Figure 2

Cost of care for ESRD patients at the end of life based on hospice utilization

Dialysis patients are much less likely to use hospice services compared to other patients with chronic illnesses.14 Compared to congestive heart failure patients, for example, ESRD patients more often die in the hospital, are more likely to undergo aggressive treatments in the last month of life, and have a lower use of hospice services.15 Of ESRD patients who die, 27 percent receive some hospice services with a median time of hospice use of five days.16 Accessing acute hospital services and lack of hospice use has not only a personal cost for patients and families, but also a significant economic cost. ESRD patients who have more than two weeks of hospice care at the end of life have a health care cost of $1,553 in the last seven days of life, compared to $11,036 if not referred to hospice until the final two days of life (Figure 2).17

As a result of passage of the Patient Self-Determination Act (PSDA) in 1990—which included a requirement for health care institutions to provide advance directive information— ESRD conditions for coverage requires dialysis facilities to have advance directive documentation for all patients. But advance care directives are only a small part of the advance care planning (ACP) process needed and desired by patients and families. ACP is a process that supports articulation of patient values, goals, and preferences for care.18 Studies have shown that the process of ACP improves patient QOL, reduces patient and family anxiety, and improves preparation for end-of-life decisions to avoid unwanted hospitalizations and procedures.19-21

In 2016, Fresenius Medical Care’s Clinical Innovation Initiatives (CII) group partnered with 20 Fresenius Kidney Care dialysis facilities as part of a quality improvement (QI) project examining patient-centered comfort care. During eight months of work with these clinics, the CII team discovered that the dialysis clinic staff often experienced both expected and unexpected patient deaths. Some patients withdrew from or stopped dialysis before death, but this most often occurred during a hospital admission where there was privacy, time for discussions with patients and families and additional resources to assist with palliative care, hospice, home health, and nursing home support. Dialysis staff work diligently to meet individual patient care needs, but it is complex to proactively “see” patients who need supportive care services.

As part of the CII project, we noted that dialysis facility staff commonly care for patients who express and exhibit pain, depression, and ambivalence about dialysis treatments. In some cases, patients and families articulate goals of care for dialysis treatments and coordinate with nephrologists and dialysis staff to modify treatment to achieve QOL goals. Often, these patients are outliers for typical clinical quality indicators such as treatment time, missed treatments, and dialysis adequacy since there is no formal program to provide treatment to meet QOL goals. During this QI project, we also discovered that patient deaths can result in staff stress and burnout related to unresolved grief issues.

Recent qualitative scientific studies have demonstrated the disparity between outcomes of interest to patients and current rehabilitative dialysis clinical quality measures.22 While current care guidelines are recommended for all patients regardless of age, prognosis, or patient preferences, many patients—especially the frail and elderly—report that QOL issues outweigh treatment goals focused on longevity.23-25 The dialysis patient population is older and sicker, but the care delivery system has not evolved to meet the needs of these patients, resulting in “impractical,” even “harmful” care for some.26-28 It has been suggested that we need to transition from “what interventions are available” to “what treatment goals are attainable and desired for this patient.”29

Meeting treatment goals is particularly complex for patients with a high symptom burden on dialysis when there is only a binary treatment choice: dialyze on the accepted best practices treatment regimen meeting clinical quality indicators, or withdraw from dialysis. The average survival after stopping dialysis is eight days, so this yes-or-no choice for patients and families is difficult. Kidney supportive care embodies an opportunity to elicit patient preferences and treatments to ameliorate symptoms and suffering, instead of asking, “Do you want to stop dialysis?”30 This is far more than a discussion about advance directives and will not be solved completely just by improving communications with patients and families.

Issues Providing Individualized Kidney Supportive Care

Based on published findings, here are some lingering issues to providing individualized kidney supportive care:31-33

- What are the criteria or “triggers” for patients to be considered for treatments other than standard rehabilitative dialysis?

- Patients and families need good prognostic information, and we have inadequate tools today.

- The care team needs more knowledge, skill, and time to have patient and family discussions.

- Supportive care delivery is fragmented among providers. Who has responsibility?

- How can we deliver such individualized care, some of which may need to occur in the patient’s home?

- Who can manage chronic pain and other burdensome symptoms?

- Metrics for “palliative dialysis” or treatments focused on symptom relief need to be developed.

- Clinical quality indicators and reimbursement need to be aligned to palliative and supportive treatments.

Over decades of progress in dialysis treatment, important achievements in clinical standards of care delivery have resulted in meaningful improvement in dialysis patient mortality. While many patients need and want rehabilitative dialysis, a growing number of patients may desire and benefit from treatment focused on QOL goals. This will require alternative quality standards of care and metrics, including alternatives to traditional rehabilitative dialysis treatment. Patient-centered kidney supportive care will meet patient and family desires for meaningful, comfortable treatment while reducing the burdens of acute end-of-life care.

Meet the Author

Dugan Maddux, MD, PhD, FACP

Vice President of Kidney Disease Initiatives

Fresenius Medical Care North America

Nephrologist Dugan Maddux champions FMCNA’s clinical innovation endeavors across the continent, and is co-founder of the Gamewood companies, including Acumen Physician Solutions. Blogger, writer and essayist, she developed the Nephrology Oral History project chronicling early dialysis pioneers and holds her BS degree in chemistry from Vanderbilt University and her MD degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

References

Moving Toward Kidney Supportive Care

by Dugan Maddux, MD, PhD, FMCP

- Prevalence and cost of ESRD therapy. Chapter 3 of USRDS 1994 Annual Data Report. https://www.usrds.org/download/1994/ch03.pdf.

- Incidence, prevalence, patient characteristics, and treatment modalities. Volume 2, chapter 1 of USRDS 2016 Annual Data Report. https://www.usrds.org/2016/view/v2_01.aspx.

- Reid, C, Seymour, J, and Jones, C. A thematic synthesis of the experiences of adults living with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(7):1206-18.

- Vandecasteele, SJ, and Kurella Tamura, M. A patient-centered vision of care for ESRD: dialysis as a bridging treatment or as a final destination? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(8):1647-51.

- Davison, SN, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference on Supportive Care in Chronic Kidney Disease: developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int. 2015;88(3):447-59.

- Chazot, C, et al. Pro and con arguments in using alternative dialysis regimens in the frail and elderly patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(11):1809-16.

- Scherer, JS, and Moss, AH. Practice change is needed for dialysis decision making with older adults with advanced kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;pii:CJN.08770816.

- Romano, TG, and Palomba, H. Palliative dialysis: a change of perspective. J Clin Med Res. 2014;6(4):234-8.

- Davison, SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204.

- Grubbs, V, et al. A palliative approach to dialysis care: a patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(12):2203-9.

- Davison, SN, and Jassal, SV. Supportive care: integration of patient-centered kidney care to manage symptoms and geriatric syndromes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016;pii:CJN.01050116.

- Hussain, JA, et al. Patient and health care professional decision-making to commence and withdraw from renal dialysis: a systematic review of qualitative research. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(7):1201-15.

- End-of-life care for patients with end-stage renal disease: 2000-2013. Volume 2, chapter 14 of USRDS 2016 Annual Data Report. https://www.usrds.org/2016/view/v2_14.aspx.

- Schell, JO, and Holley, JL. Opportunities to improve end-of-life care in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(12):2028-30.

- Scherer, JS, and Holley, JL. Improving advance care planning and bereavement outcomes.

Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):735-7. - End-of-life care for patients with end-stage renal disease. USRDS 2016.

- Ibid.

- O’Hare, AM, et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11(5):855-66.

- Ibid.

- Davison, SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs.

- Goff, SL, et al. Advance care planning: a qualitative study of dialysis patients and families. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):390-400.

- Reid and Jones. A thematic synthesis.

- Grubbs et al. A palliative approach to dialysis care.

- Davison and Jassal. Supportive care.

- Hussain et al. Patient and health care professional decision-making.

- Vandecasteel and Tamura. A patient-centered vision.

- Davison et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies Conference.

- Chazot et al. Pro and con arguments.

- Vandecasteel and Tamura. A patient-centered vision.

- Grubbs et al. A palliative approach to dialysis care.

- Ibid.

- O’Hare et al. Provider perspectives on advance care planning.

- Holley, JL, and Davison, SN. Advance care planning for patients with advanced CKD: a need to move forward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(3):344-6.