RAPID TESTING OF CLINICAL INTERVENTIONS | FMCNA

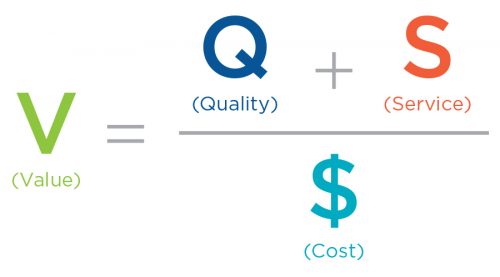

As the health care economic framework shifts from paying for volume to paying for value, the ability to quickly vet and test clinical interventions becomes increasingly important.1 Within a value-based framework, it is no longer enough to understand that an intervention improves quality. Instead, Fresenius Health Partners (FHP) is compelled to focus on the financially efficient delivery of quality. Perhaps, this is best expressed in the abstract through the simple equation:

As a company, Fresenius Medical Care North America (FMCNA) has a long and robust history of generating—and, in many cases, publishing—insights garnered from the company’s massive collection of clinical data. More recently, FHP risk arrangements have provided the organization with access to medical claims data. Combining claims data with clinical data creates an opportunity to generate valuable insights with respect to the financially efficient delivery of quality. To formalize an approach to this opportunity, FHP has created the Clinical Interventions Lab (the Lab).

The Lab is made up of individuals from across the enterprise, collectively working together to rapidly vet, prioritize, and pilot clinical interventions within the risk populations FHP serves. The Lab's foundational principles include:

Clinical Interventions Lab Framework

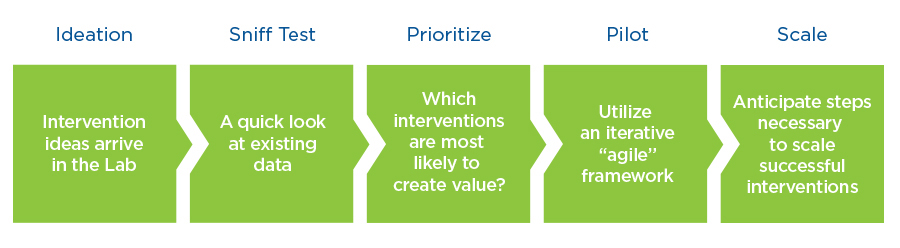

At a high level, the process in place involves five steps (Figure 1):

- Ideation: A potential intervention emerges from either within or outside the Lab.

- Sniff test: A small team takes a quick look from a clinical, financial, and actuarial perspective.

- Prioritization: If the idea passes the “sniff test,” it’s reviewed by the Lab and prioritized.

- Pilot: The majority of the clinical interventions are pressure tested with a live market pilot.

- Scale: Clinical interventions that succeed in pilot are scaled nationally.

Figure 1 | Clinical Interventions Lab Framework

During its first six months of operation, the Lab has generated several valuable insights. The first is the value of data-driven decisions. One of the early interventions FHP considered was the deployment of intensive diabetes education and management.

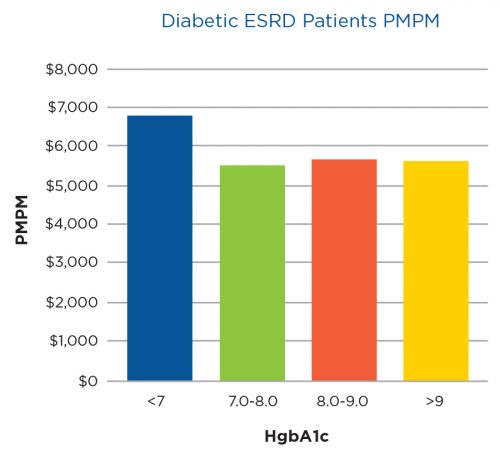

A third party shared convincing evidence that poorly controlled diabetic patients were more expensive to care for than well- controlled diabetic patients. They were able to demonstrate that their diabetes management services not only improved control, but also substantially reduced the total cost of care. The FHP team was intrigued by the possibility of deploying that service to the at-risk ESRD diabetic population.

Much to the team’s surprise, the sniff test yielded no difference in total cost of care among well-controlled and poorly controlled ESRD diabetic patients (Figure 2). The results identified in the general population were not present in the ESRD population.

That’s not to say glycemic control should be ignored in ESRD, but the Lab could not justify piloting an expensive service to advance the value equation. This is an example of using data to drive decisions, and it supports the “fail early and often” principle as well.

The Lab's Operational Pilot Touchpoints

A second valuable insight relates to the Lab’s approach to pilots. Each pilot has a champion who is committed to testing the hypothesis that the Lab is examining with a specific clinical intervention. The champion works closely with a project manager, paying attention to the following operational pilot touch points:

- Project charter—This is established at the beginning of the process.

- Stakeholders—FHP has the luxury of recruiting willing contributors from across the breadth of the enterprise.

- Duration/size—This is established based on success metrics by which the pilot will be judged.

- Legal/compliance—Both are involved at the outset, not to solve all the potential issues, but to identify them early, in anticipation of scaling the intervention if the pilot is successful.

- Information Technology Group (ITG)—ITG is also involved early, not so a system solution for the pilot may be developed, but to anticipate what will be necessary should the organization be required to scale for production.

- Clinic Readiness Assessment—FHP leverages this tool created by the FKC Operational Excellence team, not as a gating step but as a valuable set of data points to utilize as the pilot’s success or failure is reviewed.

- Conditions for Coverage (CfC)—Each intervention is compared with the Medicare CfC in order to ensure the intervention does not jeopardize them.

- Funding source—Within the risk environment, FHP has the opportunity to invest in products and services generally unaffordable in a fee-for-service world, with Legal and Finance departments clarifying the appropriate source for funding.

- Success metrics—The project team defines clear and objective clinical and financial success metrics by which the pilot will be judged.

- Productization—Each team contemplates and develops the steps necessary to make scaling a successful intervention and as seamless as possible.

- Communication plan—Each team anticipates who will be impacted and ensures that not only those individuals but also appropriate senior management are aware of the pilot and its progression.

Figure 2 | Total cost of care per month per member per month (PMPM)versus average HgbA1c

One final insight. In order to move quickly, the Lab’s approach to pilots more closely resembles an agile methodology as opposed to the classic waterfall approach to project management.2

FHP’s intent is to avoid investing substantial initial capital in developing a complex project plan that requires rigid adherence. Instead, the intent is to plunge in quickly, making adjustments to the pilot based on what is discovered along the way. FHP’s preference is to fail early rather than late and to iterate as the project progresses based on what is learned in the field.

Meet the Expert

Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA

Senior Vice President and Chief Medical Officer, Integrated Care Group

Dr. Terry Ketchersid has clinical oversight over Fresenius Medical Care North America's Integrated Care Group, leading value-based care initiatives. He received his BA in chemistry from Austin College, his executive MBA from Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and his MD degree from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School.

References

Rapid Testing of Clinical Interventions: How to Be “Clinically Nimble”

by Terry Ketchersid, MD, MBA

- Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals—HHS efforts to improve health care.

N Engl J Med. 2015;372:897-899. - Stickdorn M, Schneider J. (2011) This Is Service Design Thinking. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.