SCALABLE SAFETY: 5-DIAMOND

Almost 20 years ago, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published To Err Is Human, a landmark report that estimated the annual number of deaths from medical errors at nearly 100,000. The IOM challenged the health care industry to acknowledge its intrinsically risky nature and make it easier for clinicians to do the right thing.1 An important recommendation highlighted in the report was that health care organizations, like other high-risk industries, must cultivate a “culture of safety.” The American Nurses Association defines a culture of safety as “core values and behaviors resulting from a collective and sustained commitment by organizational leadership, managers and health care workers to emphasize safety over competing goals.”2 It is a core mechanism underlying safe, effective, and timely patient care.3

Like many concepts integrated into the patient safety movement, the concept of a culture of safety originated in aviation. Through accident investigations, researchers realized that accidents were not caused by bad people. Rather they were determined by the interactions of many moving parts, or systems, modified by crews’ perceptions of hierarchy, production pressures, and fatigue.4 That is, systems made flights safe or unsafe; culture determined how effectively crew members could compensate for unsafe systems and ultimately fix them. In health care, organizations with a strong culture of safety are committed to resolving the underlying, systemic causes of error.5 They are characterized by allocation of resources for patient safety work; open, blame-free communication about risk; a nonpunitive approach to investigating and learning from mistakes; and continuous efforts to design safer systems.6 Through patient safety research over the last two decades, we now have a better understanding of how we might intervene in safety culture locally and take those interventions to scale.

Fresenius Kidney Care (FKC) recognizes the benefits of a company-wide culture of safety. To set the standard in patient safety by which others in the health care industry are judged, this work cannot simply be delegated to a department. From boardroom to chairside, everyone in FKC has a role to play in the development of a company-wide culture of safety. FKC made a clear commitment to this via its support of the 5-Diamond Patient Safety Program, an ESRD Networks-sponsored program that introduces patient safety principles to frontline staff. FKC can build on that program’s success and take a culture of safety to scale by clarifying team members’ roles and responsibilities across all levels of the organization.

Strengthening Local Safety Culture

During the 2016 FKC clinical managers’ meeting, executive leadership made a commitment to promote, enhance, and raise awareness across the organization regarding our culture of safety. In keeping with that commitment, FKC launched the 5-Diamond program, consisting of five education modules rolled out throughout 2016. The modules identified attributes of a positive safety culture:

- Pervasive commitment to patient safety: Needed resources are committed, including time and technology. Expectations of physicians, staff, and patients are clearly communicated. Policies and procedures support the same.

- Open, blame-free communication: All levels of facility staff are encouraged to voice concerns without fear of retribution.

Patients and families feel free to ask questions whenever “something does not seem right.” A grievance system is in place that encourages patients to express concerns freely without fear of reprisal. A safe environment is not error-free. - A just culture environment: Human errors are identified and discipline is applied appropriately after a systematic review of the error. The module’s “Peer Review and Root Cause Analysis” is used to effectively evaluate whether errors occurred as system/ process or human failure. Staff are held accountable for their actions or behaviors but are held blameless when there is a system or process that allowed the error to happen.

- Safety design: This assures the identification and resolution of system issues, length of workdays, heavy workload, sources of distraction, turnover, and overutilization of agency staff. It focuses on processes through the evaluation of work flow—the number of steps and number of people involved in situations. It reduces variation through the use of protocols and checklists, promotes standardization and benchmarks, and evaluates what works elsewhere.

A facility-wide culture of safety enables complete staff and patient engagement, ensuring to assure that everyone is committed to identifying and mitigating any risk to patients. Of the 98 percent of FKC facilities that participated in the 5-Diamond Patient Safety Program, 99 percent achieved 5-Diamond status in 2016, a distinction rate far ahead of any of our competitors. The safety program was a critical strategic investment because it trained our frontline staff to see patient safety and outcomes as the product of systems, and introduced key patient safety concepts at the local clinic level.

Interventions to cultivate a culture of safety must live and thrive within discrete dialysis work areas because safety culture is local. In the hospital setting, patient safety researchers have confirmed that perceptions of safety culture vary from unit to unit, even within the same hospital.7 This variation likely exists because a culture of safety originates in safety climate, or staff members’ shared perceptions of whether their direct leadership truly prioritizes patient safety above other organizational goals.8 Staff perceptions are shaped by what their direct leadership messages, what they devote resources to, and what they hold their team accountable for. Those perceptions guide how frontline staff behave on the job. For example, a patient care technician (PCT) is more likely to wash her hands according to protocol if her clinical manager has demonstrated that patient safety is the clinic’s priority.9

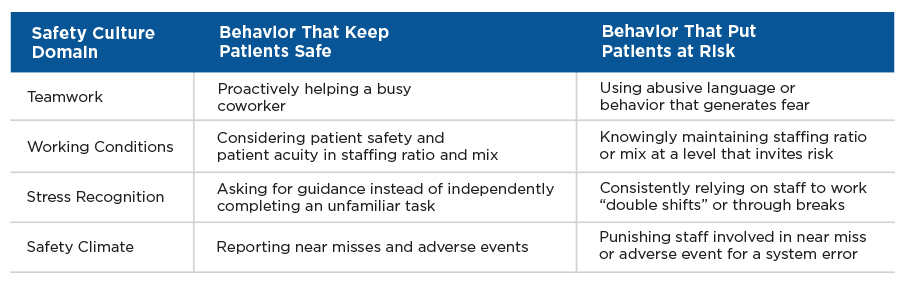

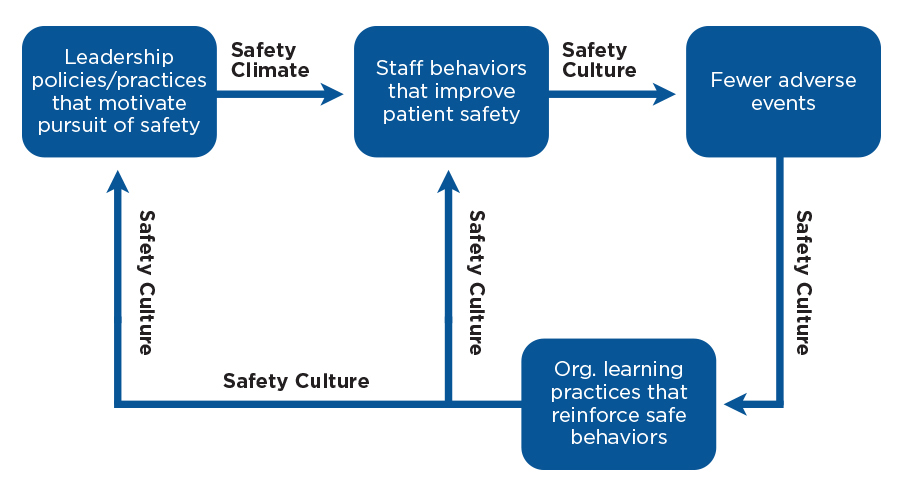

Safety climate becomes safety culture as staff perform behaviors that make patients safer (Figure 1) and the organization learns from their experiences, creating a feedback loop to leadership and staff. The cycle strengthens a culture of safety as the organization gets measurably better and better at keeping safe (Figure 2).10

Cultivating a Culture of Safety From Boardroom to Chairside

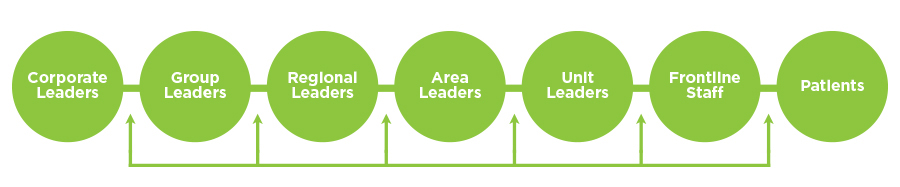

Because shared perceptions of direct leadership priorities are the origin of safety culture, health care organizations must clarify patient safety goals, roles, and responsibilities across organizational levels. A clinical manager, for example, will have a harder time conveying the importance of patient safety to her staff if her director of operations only talks to her about productivity—and so on up the chain of command. To build on the success of the 5-Diamond Patient Safety Program, FKC can continue to develop the capability within clinic-level teams to do patient safety work and create a chain of accountability for patient safety efforts that connects all levels of the organization (Figure 3).11 As FKC leadership clarifies roles and responsibilities, it must also ensure that staff and leadership have the skills, time, and resources to conduct and lead patient safety work.

Figure 1 | Staff behaviors by safety culture domain

Figure 2 | Safety culture cycle (Adapted from Vogus et al., Doing no harm.10)

One of the most accessible and compelling evidence-based interventions to improve safety culture and make patients safer is the creation of a unit-level process to engage frontline staff in patient safety and quality improvement efforts.12 Clinic-level leadership can drive ongoing employee engagement in patient safety efforts by asking frontline staff to identify defects in the unit-level system and then fixing the defects they identify. Surgeon leaders at the Johns Hopkins Hospital were able to dramatically reduce their surgical site infection (SSI) rates by asking frontline staff, “How will the next patient develop an SSI?” and structuring improvement interventions around staff responses.13 Their experience demonstrated the power of bottom- up, frontline staff-driven quality improvement.

The Johns Hopkins story also demonstrated that although clinicians and patients identify problems at the unit level, they cannot all be solved with unit-level resources.16 Some SSI interventions required leadership engagement at the departmental or hospital level. In dialysis, some clinic-level defects will require support from area and regional leadership to address.

Going up the chain of shared accountability from frontline staff to corporate leadership, each level is accountable for reporting safety concerns that cannot be fixed with available resources. These efforts are supported by an internal transparent reporting process. Going down the chain from corporate leadership to frontline staff, each level is accountable for clarifying patient safety goals, providing resources to enable patient safety efforts, and reviewing performance (e.g., regional leadership routinely reviews all adverse events within its region).14 Interventions to improve a culture of safety must thrive at the unit level, but they require alignment of support and resources across the organization.

Figure 3 | Chain of shared accountability for patient safety efforts

Conclusion

Since To Err Is Human was published, the health care industry has become safer but can do more to achieve high reliability.15 FKC—with its people, structure, and access to data—is well- positioned to lead the industry toward safer care. FKC leaders can support a continuously improving, effective safety culture by ensuring that all staff members understand what their safety responsibilities are. This starts with leadership commitment that reflects their beliefs, attitudes, values, and principles about safety in the form of organization-wide policies and practices. FKC has made a commitment to promoting the culture of safety within its facilities with the success of the 2016 5-Diamond program— and a commitment to continue supporting the program on an ongoing basis.

FKC leadership shares the accountability and success of the program by getting employees involved in improving and maintaining the safety culture. The organization must continue to let everyone know that the well-being of patients and the quality of care they receive is the organization’s goal and reason for being. The culture of safety within the dialysis facility should be the first thing staff think about when they come to work and the last thing they think about before going home. It’s a tone continuously supported by corporate and operational leadership, not something that is only talked about occasionally. Employees should embody the FKC mission statement and be committed to delivering superior care that improves the quality of life of every patient, every day, setting the standard by which others in the health care industry are judged.

Meet the Author

Kathleen Belmonte, MBA

Vice President of Clinical Services

Fresenius Kidney Care

Kathleen Belmonte brings 20 years of health care experience to her role in leading clinical services for FMCNA’s kidney care division. She is the former Chief Operating Officer for Immediate Care, LLC and served in senior executive roles in the diabetes medical supply and pharmaceutical space. A certified Family Nurse Practitioner and Diabetes Educator, she holds her MBA from Babson College.

References

Scalable Safety: 5-Diamond

by Kathleen Belmonte & Kathryn Taylor

- Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson, MS. (2000). To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.17226/9728.

- 2016 culture of safety—January. American Nurses Association Web site. http://www. nursingworld.org/CultureofSafety-January. Accessed March 30, 2017.

- Braithwaite J, Westbrook MT, Travaglia JF, Hughes C. Cultural and associated enablers of, and barriers to, adverse incident reporting. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(3):229-233.

- Sexton JB, Thomas EJ, Helmreich RL. Error, stress, and teamwork in medicine and aviation: cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 2000;320:745-749.

- Singer S, Vogus T. Reducing hospital errors: interventions that build safety culture. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013;34:373-96.

- Sutcliffe K. High reliability organizations. Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2011 June;25(2):133-144.

- Singer S, Gaba D, Falwell A, et al. Patient safety climate in 92 US hospitals: differences by work area and discipline. Med Care. 2009;47(1): 23-31.

- Singer, Vogus. Reducing hospital errors.

- Daugherty EL, Paine LA, Maragakis LL, et al. Safety culture and hand hygiene: linking attitudes to behavior. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012 December;33(12):1280-1282.

- Vogus TJ, Sutcliffe KM, Weick KE. Doing no harm: enabling, enacting, and elaborating a culture of safety in health care. Acad Manage Perspect. 2010 November;24(4):60-77.

- Pronovost P, Marsteller J. Creating a fractal-based quality management infrastructure.

J Health Organ Manag. 2014;28(4):576-586. - Pronovost P, Weast B, Rosenstein B, et al. Implementing and validating a comprehensive unit-based safety program. J Patient Saf. 2005 March;1(1):33-40.

- Wick E, Hobson D, Bennett J, et al. 2012. Implementation of a surgical comprehensive unit-based safety program to reduce surgical site infections. J Am Coll Surg. 2012 August;215(2):193-200.

- Vogus, Sutcliffe, Weick. Doing no harm.

- National Patient Safety Foundation. Free from harm: accelerating patient safety improvement fifteen years after To Err Is Human. Report of an expert panel convened by the National Patient Safety Foundation, February 2015. http://www.npsf. org/?page=freefromharm. Accessed March 30, 2017.

- Pronovost, P. J., Weast, B., Bishop, K., et al. (2004). Senior executive adopt-a-work unit: A model for safety improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Saf, 30, 2, 59–68.